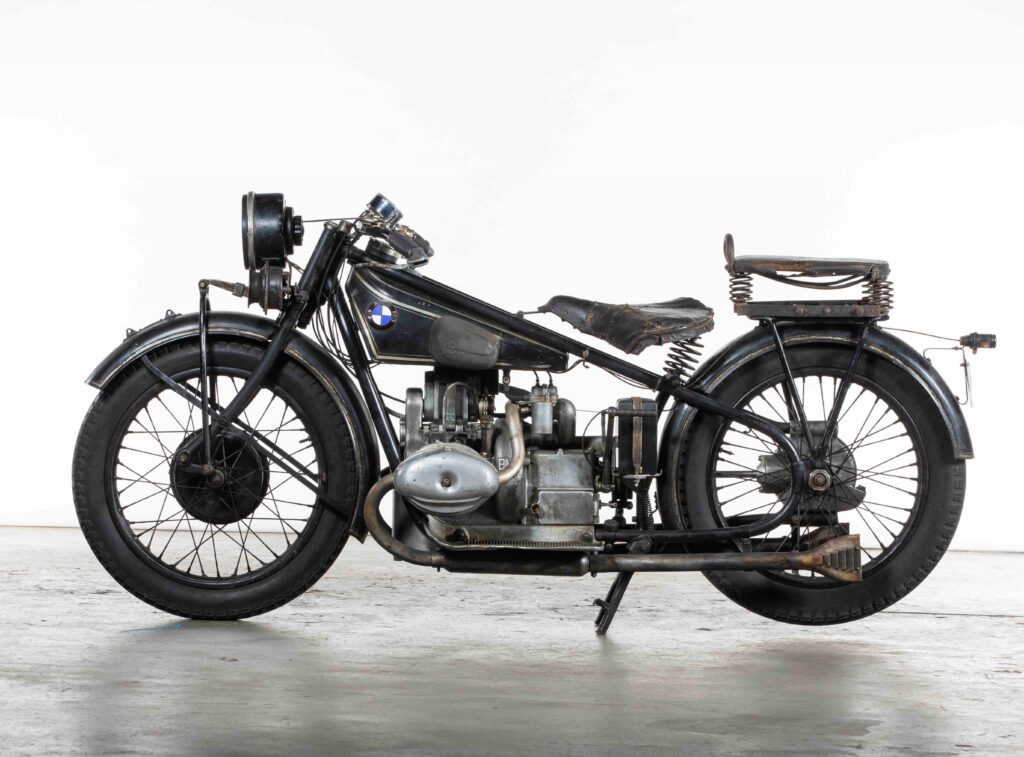

1923 – ’28

First motorcycles from Munich

During World War I, BMW rose to prominence as a manufacturer of high-altitude airplane engines designed by Max Friz. Germany’s defeat in 1918 saw BMW’s business model shattered, leaving the company desperate for new products that wouldn’t fall afoul of the Treaty of Versailles’ restrictions on military production.

Engineer Martin Stolle suggested a small-displacement, opposed-twin engine like that in his beloved Douglas motorcycle. The resulting M2B15 engine was sold by BMW to customers including Victoria and BFW. BFW was owned by BMW’s principal shareholder Camillo Castiglioni, who merged the two companies in 1923. Rather than continue to build the BFW Helios, Friz designed an all-new motorcycle worthy of the BMW roundel. Introduced in 1923, the R32 created a template for BMW motorcycles that serves to this day, with a boxer engine mounted transversely in the frame and shaft drive to the rear wheel.

Having completed the R 32, Friz returned to his beloved airplane engines, leaving the motorcycle division to young engineer Rudolf Schleicher . Schleicher took BMW in a decidedly sporting direction, turning Friz’s R 32 into the race-winning R 37. By the time Schleicher left BMW in 1927, the company’s race team was utterly dominant on the Grand Prix racing scene.

In 1929, factory rider Ernst Henne and his aerodynamic R 47 set BMW’s first world speed record with a run at 137 mph, which be bested with a second world record run at 138 mph in 1930.

Equally important, BMW’s side-valve engined touring bikes like the R 42 were considered the finest in Europe, revered by long-distance riders for comfort and reliability.

1929 – ’41

The Golden Age

The crash of the US stock market in October 1929 marked the beginning of the Great Depression that would define the 1930s. The economic crisis was felt worldwide, but BMW was well-positioned to weather the storm thanks to motorcycles that remained highly desirable even under trying circumstances. That desirability was due in no small part to a stylish new pressed-steel frame introduced in 1929. Borrowing technology from the auto industry that BMW had joined only a year earlier, the “Star” frame gave motorcycles like the R 11 a distinctly modern look. The pressed-steel frame defined BMW in the early 1930s, and it set an aesthetic standard for all German motorcycles that would last for decades.

Equally important, BMW began building a new series of affordable single-cylinder motorcycles, starting with the R 2 designed by Alfred Böning to take advantage of license and tax exemptions for sub-200cc machines. Larger-displacement singles would follow, with the 350cc R 35 becoming especially popular with off-road riders and the military after 1937.

The return of Rudolf Schleicher to BMW after four years at Horch forced BMW Motorrad to choose a direction. Böning favored high-end touring bikes for the autobahn, exemplified by his dramatically-styled R 7 concept of 1934. The R 7 introduced hydraulically-damped forks and a four-speed transmission built as a single unit with the 793cc engine.

Schleicher advocated a return to sport bikes, and he ultimately won the day. The R 7 remained a concept, while Schleicher’s 1936 R 5 introduced a welded steel-tube frame along with a new 500cc boxer engine. The R5 dominated the racing scene almost immediately—thanks in no small part to its use of Böning’s telescopic forks and four-speed gearbox.

Schleicher resumed his earlier experiments with supercharging, building a forced-induction M255 engine for the streamliner ridden by Ernst Henne to his seventh and final world speed record in 1937. Henne’s time of 174 mph wouldn’t be broken for a remarkable 14 years.

Schleicher’s development of the R 5 culminated with the supercharged Type 255 race bike. After winning Grand Prix races for Otto Ley and Karl Gall in 1936 and ’37, the Type 255 carried Schorsch Meier to the German and European championships in 1938, and to victory in the 1939 Isle of Man Senior TT. Had Meier not been injured in a crash in Sweden, he’d have surely repeated as European champ in 1939.

It was a great run, but it wasn’t to last. World War II put an end to racing in 1940, and BMW was forced by the Nazi military authorities to abandon civilian cars and motorcycles in favor of airplane engines and motorcycles like the R 75 for the German military. Complicit in a war that left ten million dead and two continents in ruins, BMW would be nearly destroyed by Allied bombing just five years later.

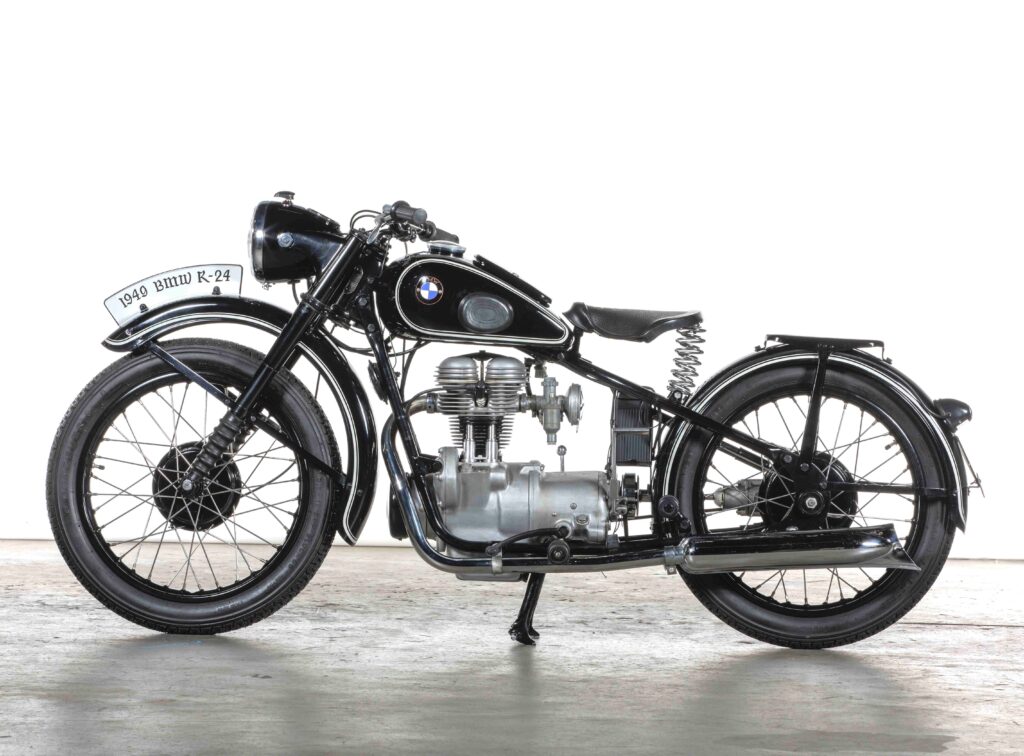

1948 – ’68

Post-war resurrection

By the time Munich fell to the Allies in May 1945, BMW’s home plant had been largely destroyed by Allied bombing. It was slated for demolition until managing director Kurt Donath persuaded the US Army to allow production first of household goods, then bicycles, and finally a small motorcycle. One problem remained: In 1941, BMW had moved motorcycle production from Munich to its plant in Eisenach—now lost to the Soviets, along with BMW’s engineering drawings for motorcycles. To build new bikes, Alfred Böning’s team measured every nut and bolt on a prewar R 23 single, improving the bike along the way. In spring 1948, the 247cc R 24 debuted at the Geneva motor show; by the end of 1949, BMW had built 9,144 examples.

In 1950, Böning followed with BMW’s first postwar boxer twin, the R 51/2 that would be superseded a year later by the further-evolved R 51/3.

As BMW recovered along with the German economy, racing again became a priority. Though the prewar Type 255 was still winning German titles for Schorsch Meier and his factory teammates, a new generation of racers was coming to the fore, led by Walter Zeller, who beat Meier to the German 500cc title in 1951.

In 1954, BMW introduced the RS 54. It wasn’t sharp enough to score Grand Prix wins, but the RS 54 won all but one 500cc German national championship from 1954 to ’62: two more for Zeller, one for Ernst Riedelbauch, four for Ernst Hiller, and one for Hans-Gunther Jäger.

The RS 54’s Type 253 engine proved ideally suited to sidecar racing, and in 1954 it powered Wilhelm Noll and Fritz Cron to their first world championship. Thus began a run of success for BMW-engined sidecars that wouldn’t end until 1974, making champions of Walter Schneider, Max Deubel, Klaus Enders, and Helmut Fath. Privateer Fath was a particularly innovative engineer, developing the Kneeler sidecar that revolutionized the sport in 1960; later, he built the URS engine that dealt BMW its only losses in 1968 and ’71.

For the street, BMW’s boxer-engined touring bikes regained their prewar prominence among long-distance riders. In 1952, the 35-horsepower R 68 became Germany’s fastest motorcycle with a top speed of nearly 100 mph. In 1955, BMW introduced its first models with Earles forks and swingarm rear suspension; the upgrade allowed the R 50, R 60 and R 69 to remain desirable through the end of the 1960s, especially the sportier models like the R 50 S.

BMW’s motorcycle engines also provided motive power for a line of microcars introduced in 1954. The Isetta 250 borrowed its single-cylinder engine from the R 25 motorcycle, while the 600 and 700 used a boxer twin derived from that in the R 50. These microcars were crucial to BMW’s survival in the late 1950s, when its premium-focused automotive strategy proved almost fatally flawed. Sales of the 700, in particular, kept BMW afloat until the midsize Neue Klasse sedan could be launched in 1962.

1969 – ’89

Bikes from Berlin

By the mid-1960s, BMW’s bikes had become rather staid despite the modernizing efforts of engineers like Helmut-Werner Bönsch, and they weren’t selling well, either. To save its motorcycles from extinction, BMW took advantage of a federal tax credit to move motorcycle production to an underused factory in Berlin. At the same time, BMW updated its lineup with the all-new /5 engineered by Bönsch and Motorrad boss Hans-Günther von der Marwitz. The /5s were an immediate success, and they revitalized BMW as a motorcycle manufacturer.

So did the 1972 arrival of Bob Lutz (left), an enthusiastic motorcyclist serving as BMW board member for sales and marketing. Lutz backed Marwitz’s evolution of the /5 into the /6, and he commissioned stylish bodywork for the flagship R 90 S from designer Hans Muth. The R 90 S became a design icon for BMW, as well as a standard-bearer for performance. Heavily modified by US importer Butler & Smith, an R 90 S ridden by Reg Pridmore won the very first AMA Superbike Championship in 1976.

For his next act, Muth designed the world’s first fully-faired touring bike, the R 100 RS (left) refined in the Pininfarina wind tunnel. Before the decade was out, Muth would also design the groundbreaking R 80 G/S, BMW’s first bike dedicated to long-distance riding over pavement and dirt. At Muth’s insistence, the G/S was equipped with a single-sided swingarm that simplified rear-wheel removal—an important consideration off-road. Like the R 90 S, the G/S became a race winner, taking victories in the challenging Paris-Dakar Rally with Hubert Auriol in 1981 and ’83, and in 1984 with Gaston Rahier.

By then, Muth had been succeeded by Klaus-Volker Gevert as BMW Motorrad’s lead designer. Gevert took over just as BMW was in the midst of revolutionizing its lineup yet again, this time under the direction of new BMW Motorrad chief Richard Heydenreich and head of development Stefan Pachernegg. Responding to increasingly stringent noise and emissions regulation, they designed the 1983 K 100, the first in an all-new series of bikes powered by inline four- or three-cylinder engines. Though they departed dramatically from BMW’s boxer twin tradition, the K-bikes were well received by BMW traditionalists thanks to their reliability and long-distance comfort.

In 1989, the first-generation K-bikes reached their zenith with the K1 , which featured fully-enclosed aerodynamic bodywork as well as BMW Motorrad’s first four-valve engine and Bosch digital motor electronics. In 1988, BMW’s K-bikes became the world’s first motorcycles with ABS.

1989 – 2004

Boxer renaissance

The success of the K-bikes, and the ease with which their liquid-cooled engines could meet stringent emissions standards, seemed at first to spell doom for BMW’s long-running air-cooled boxer twins.

In 1989, however, the appointment of Dr. Burkhard Göschel as head of BMW Motorrad saw a breakthrough in the development of a modern boxer engine. Göschel’s “oil head” boxer used a secondary lubrication system to supplement passing air in cooling the four-valve cylinder heads. The system made the engine quieter and more efficient, as well, especially with fuel injection in place of carburetors.

Installed in the 1993 R 1100 RS, the oil-head engine signaled a renaissance for the boxer twin, but the engine wasn’t the bike’s only novel feature. It also introduced a new front suspension system dubbed the Telelever (right), which reinterpreted the Earles concept to eliminate fork dive under braking.

Shortly after the R 1100 RS debuted, David Robb was appointed head of BMW Motorrad design. Robb brought an entirely new sense of style to BMW’s motorcycles. He signaled his intentions with the 1996 K 1200 RS which launched to broad acclaim thanks to its sleek bodywork and comfortable ergonomics.

Under Robb’s tenure, BMW Motorrad expanded into new arenas, including the cruiser market with the 1997 R 1200 C and the scooter market with the 2000 C1. Neither was an enormous sales success, but they brought BMW to the attention of riders who might not have considered the marque otherwise.

Single-cylinder motorcycles were revived, too, first with the Aprilia-built Funduro in 1993 and from 2000 with BMW’s own F 650 GS dualsport and F 650 CS city bike. Richard Sainct rode a factory F 650 to Dakar Rally wins in 1999 and 2000. The boxer-engined GS, meanwhile, became a large, long-distance touring bike with dirt-road capability, and 1,200cc of displacement by 2004.

In 1998, BMW offered its first real sport bike in decades. With 98 horsepower, the R 1100 S wasn’t as powerful as a Ducati, but it was a welcome alternative to mainstream sport bikes, and it opened the door to the even-sportier machines BMW would launch a decade later.

2005 – ’23

Technology meets tradition

In the 21st century, BMW Motorrad has continued to diversify its model range. In 2006, BMW collaborated with Aprilia for a new line of single-cylinder motorcycles. The G 650 X and GS—some made in China—were discontinued in 2018; today, BMW offers the made-in-India G 310 as its entry-level model. In 2007, BMW purchased Husqvarna, but sold the venerated Swedish marque in 2013 as dirt bike sales fell dramatically in Europe.

In 2008, BMW introduced its first parallel twin-cylinder engines, installed in the agile-handling F 800 S, ST, GS, GT, and R midsize models. Today, BMW offers parallel twins from 750 to 900cc in GS and R models.

Parallel twins haven’t supplanted the traditional boxer-engined GS, and the R 1250 GS remains the gold standard among long-distance adventure riders. Today’s R 1250 engine uses the innovative Shift-Cam technology and selectable riding modes to make the GS, R, and RT smooth-running and versatile.

In 2009, BMW introduced its first sport bike with an inline four-cylinder engine: the S 1000 RR. Built to race in World Supersport and Superbike, the S 1000 RR has proved particularly competitive in the near-stock Supersport category, taking the 2010 world title with Ayrton Badovini. More recently, the S 1000 RR benefitted from a crossover with BMW’s high-performance M division, which applied its expertise in aerodynamics and carbon fiber construction to create the even more track-focused M 1000 RR.

While taking that sporting turn, BMW didn’t neglect its traditional touring constituency. In 2011, BMW introduced the K 1600 GT, its first motorcycle equipped with a six-cylinder engine. Today, the K 1600 is offered in GT, GTL, and B variants, alongside the boxer-engined R 1250 RT.

In 2012, after nearly 20 years under David Robb, BMW Motorrad got a new head of design. Edgar Heinrich brought edgy style and high-tech flair to BMW’s motorcycles, yet he didn’t neglect BMW tradition. In 2013, for the 90th anniversary of BMW Motorrad, Heinrich brought forth the retro R nineT, a stunningly simplified street bike that echoed the bikes built in Munich from 1923 through 1969.

In 2020, the R nineT was joined by a second heritage model, the R 18. With BMW’s largest-ever boxer engine, the R 18 recalls the great touring bikes of the 1920s and ’30s, bringing BMW Motorrad full circle as it celebrates its 100th anniversary.

— Jackie Jouret. All rights reserved.